By Joshua Ciappara, The University of Sydney

The six weeks of mathematical research I undertook over this last summer permitted me numerous important personal insights – on the nature of abstract problem-solving, on the dynamics of working with collaborators towards a common goal, and on what might lie ahead for me in terms of a career. But more than that, the enterprise prompted me to reflect on why I dedicate myself to the study of mathematics.

When telling friends about my career intentions – and particularly when telling them what I did with myself during January – the response is commonly follows one of two lines:

- “Maths research? Don’t we already know everything about maths?”

- “Maths research? What, do you just stare at a whiteboard all day?”

The misconception underlying response 1 is that mathematics is an elementary and quite classical branch of knowledge whose primary modern function is to lubricate the engines of the physical sciences (the progressions of which are far better known and more widely reported). I must admit that I love divesting people of this particular belief, usually by citing a famous and easily understood unsolved problem in pure mathematics; the Goldbach conjecture or Collatz conjecture are two favourites. And when they get it, and in the best instances appreciate the intrinsic beauty of the problem, I’m prone to a strident declaration: “See? Maths is really like an iceberg, and we’ve hardly chipped the surface!” The enduring mysteriousness of mathematics is one of its key appeals for me, no doubt.

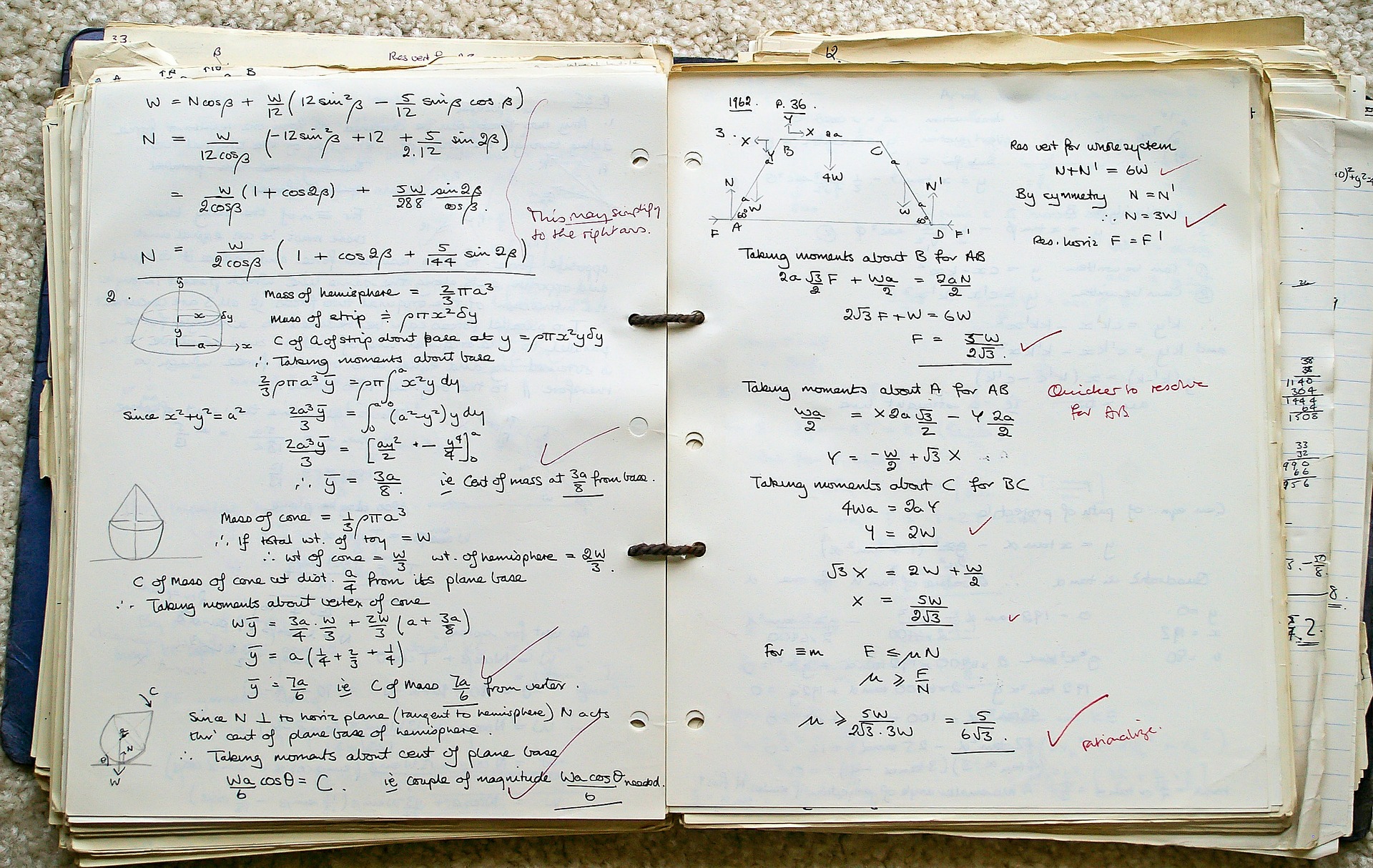

People adopting response 2 are really not far off the mark, in one sense. When I confirm their suspicions, they’re sometimes underwhelmed – but there’s simply no denying that maths research entails a lot of mental struggle and flat-out frustration. Sometimes, nothing seems to work, and the world seems like a very dark place very suddenly. What makes it all worth it, then? Because the opposite of vexation is so sublime. “Think about it”, I say. “When the ideas are flowing, you can start with a blank piece of paper and ten minutes later have figured out a universal truth. Something that was true before the Earth existed and that will be true after it is destroyed; something that is certain, indisputable, and uncompromising.” The timeless rigidity of maths is enchanting and romantic to me in a way few other things in life ever can be.

This semester I’ll be starting as a university tutor. My hope is to be able to convey something of what I’ve learned through my research project, or otherwise understood more deeply, to students just beginning their tertiary study. And I hope I’ll have the chance to answer questions like the above, so that some of them might consider a major in maths or even the possibility of research.

Joshua Ciappara was one of the recipients of a 2014/15 AMSI Vacation Research Scholarship.